The Blind Reviewing the Blind

By: Dr. Magdalen Normandeau

The blind leading the blind seems like a bad idea. Is the blind reviewing the blind any better?

The argument in favour of the double-blind review process is that reviewers can’t be impartial if they know who the authors are. If the authors are well-known and their work is generally respected, reviewers may be more lenient than is warranted for a particular submission. Conversely, there are concerns that a reviewer could let negative personal feelings toward an author colour their judgement. But do these concerns outweigh the downsides of double-blind reviews?

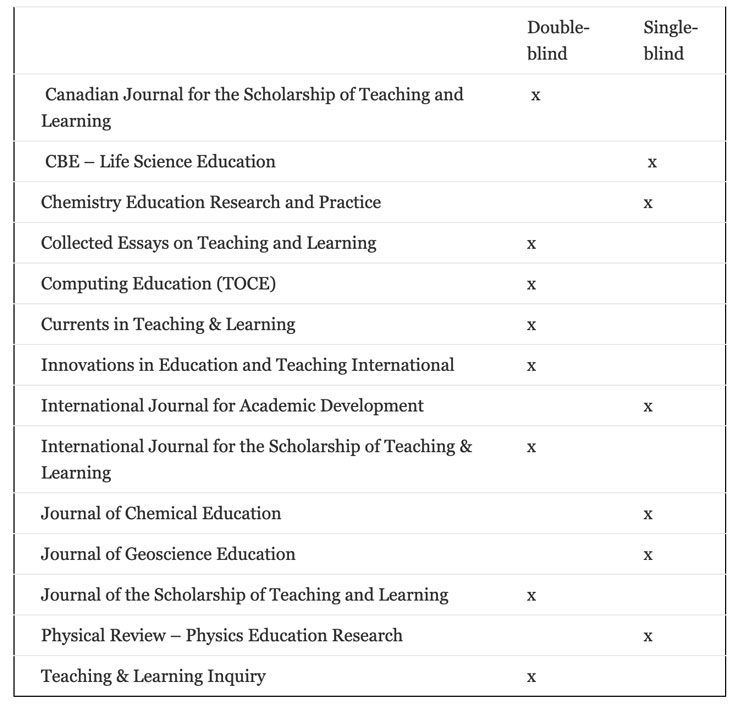

I conducted a small survey about the reviewing practices in SoTL and in Discipline-Based Education Research (DBER) journals. Here’s what I found for 14 journals:

It’s interesting to note that all but one of the SoTL journals on my list use double-blind review, whereas only one of the DBER journals uses double-blind review. This isn’t overly surprising: despite claims of being interdisciplinary and valuing the approaches of the various disciplines, SoTL methods are heavily biased toward the social sciences, where, I’m told by colleagues in those fields, journals are double-blind. This contrasts with my original field of scholarship; none of the astrophysics journals are double-blind. My point is that we don’t have to stick with the double-blind review process for SoTL just because “that’s how it’s always done.” It isn’t how it’s always done; we can choose to move SoTL journals to a single-blind review process if we decide that the costs of double-blind outweigh the benefits.

The most obvious disadvantage of a double-blind review process is that references pointing to previous work by the authors are suppressed from the bibliography. For instance, I have seen a manuscript where it was written that the intervention “was introduced using the same instruction sheet (Author, year).” Wouldn’t it have been helpful for the reviewer to be able to see that instruction sheet or read a description of it? If references are important for the reader (why else would they be included?), then, surely, they are essential for the reviewer who is tasked with assessing the quality and importance of the work. Suppressing references hamstrings the reviewer.

When I brought up the topic of double-blind review at STLHE-2019, a few people volunteered that the first thing they do when they get a paper to review is some internet searching to figure out who the author is. If this is common practice, why are we bothering to pretend that the process is double-blind?

There is a second disadvantage to double-blind reviews, one that is particularly relevant for SoTL: context matters in SoTL. In order to be able to properly assess how general an author’s conclusions are and how transferable they are, the reader needs to have a clear picture of the context in which the study was done. In Canada, it can be almost impossible to provide enough information about context without divulging the institution. For example, “this study was conducted at a mid-size comprehensive university in the Maritimes” narrows things down very quickly to UNB. For many studies, it would matter that 97% of UNB’s students are Canadian, that 74% are from New Brunswick, and that over a third are the first in their family to go to university, but I couldn’t reveal any of these details because that might allow the reviewer to identify me. Personally, I don’t mind if the reviewer knows who I am; I do mind if they don’t fully understand my study and its context.

I think it’s time to revise the practices of some of our SoTL journals. Discuss!

Author bio:

Magdalen Normandeau is a physics instructor at the University of New Brunswick and an associate editor for CJSoTL, a journal that uses the double-blind review process. Magdalen has the (bad?) habit of asking why we do things the way we do and not leaving well enough alone.